This One Image Seems to Have Asheville Scared $#!&less. Here’s Why It Shouldn’t Be.

December 26, 2024

This member commentary post does not necessarily reflect the views of Asheville For All or its members.

We’ve now had one year to observe Asheville’s response to the Missing Middle Housing Study that its city council commissioned, a study that also included a “Displacement Risk Assessment.”

The response has been underwhelming. Not one change has been passed by the city.

And to add insult to injury, some city leaders have signaled that they believe their inaction to actually be in service of “anti-displacement.”

Some time in the fall, I came to the conclusion that no one—not city staff, not the city manager, not city council—had read the Missing Middle Housing Study (and the Displacement Risk Assessment found within) at all. What else could explain their apparent erroneous understanding that “missing middle” reforms would need to wait in order to prevent the displacement of residents drowning in housing costs and lacking housing options?

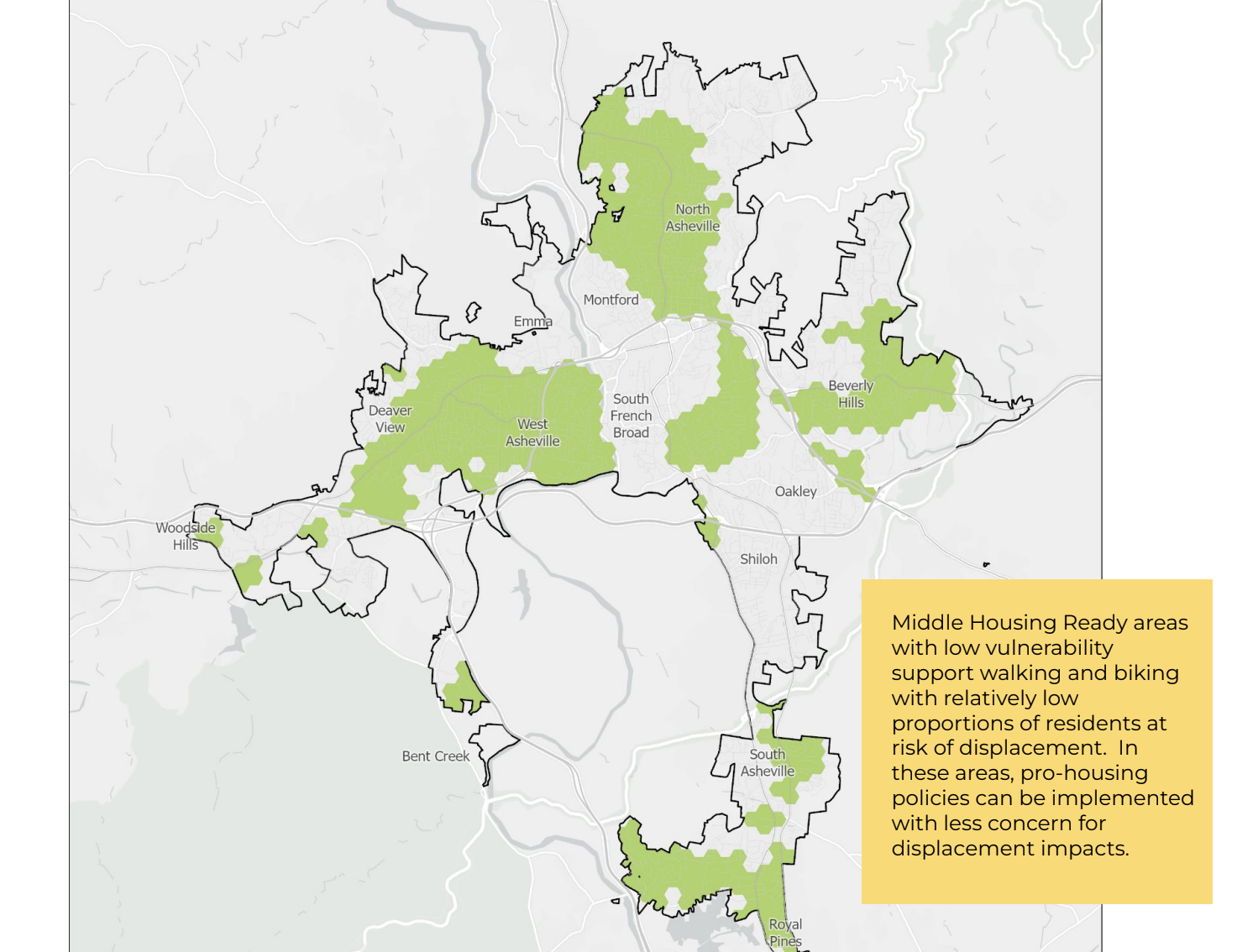

I wonder now if the problem is a little more nuanced. I thought back to some presentations that the city gave on the report in the spring and remembered that these presentations featured one particular image from the Displacement Risk Assessment. I found it irksome. It occurred to me that this was an image that, if not read in the proper context, could scare the pants off of you. And I suspect that might be what happened to our leaders.

Here it is:

So I want to talk about why this image shouldn’t be scary, in two parts—first, from the perspective of the study’s authors, to show just how clear they are on the urgency of missing middle reforms; and then from a perspective that is contrary to them, to show how their presentation of the facts, perhaps unintentionally, muddied the situation for their readers.

1. The Anti-Displacement Study Is Clear: The Solution Includes Missing Middle Reform in ALL Appropriate Neighborhoods

At first glance, this image presents some confusing ideas. Housing construction, it would seem, is both the solution and the cause of housing woes!

In case it’s not clear why this is scary to city staff and elected officials: It effectively presents housing as a trolley problem. It warns that something should be done to alleviate our housing problem, but then stresses that you can make things worse for some people if you’re not careful. This is all it would take to make leaders freeze up.

There’s a really big discussion to be had here, about all the reasons why this housing contradiction appears to some to be the case in many cities around the country, and why sometimes this is true and sometimes it’s a confused case of correlation vs. causation. So I want to keep the discussion manageably narrow here. (If you’re looking for a broader discussion, the “Supply Skepticism Revisited” study from last year is a good place to start. Or, here’s an explainer that’s a bit more “visual.” I’ll also plug Asheville For All’s own list of links here.)

The concern in the purple image is that “in some cases,” new construction increases displacement among lower-income households. Let’s set aside whether or not this is true—I’ll have more to say about this in the next section. The solution, the image then suggests, is that “pro-housing policies can be targeted at low vulnerability areas” and/or can be accompanied by “anti-displacement strategies.”

It’s not immediately clear what those anti-displacement strategies might be from this image, but the prior suggestion is clear enough: targeting pro-housing policies at low vulnerability areas means that you allow or incentivize more multifamily housing to be built in wealthier, more in-demand neighborhoods.

Personally, I’d have no issue if tomorrow the city simply decided to “upzone” (that is, apply pro-housing reforms and incentives to allow more multifamily and small lot housing to be built) the wealthier spots of North Asheville and West Asheville. It would sure seem to fit the framework being suggested here. It would be a big improvement over the status quo, where we haven’t seen much new infill housing in the city’s most in-demand, job-and-amenity-rich neighborhoods.

But were one to read the Displacement Risk Assessment closely, there’s some important points that the study makes.

First, it points out that the more broadly pro-housing reforms are made, the less likely any displacement is going to happen (97). We’ve talked about this before on the blog. Recent research from Minneapolis, MN to Auckland, New Zealand confirms it to be true.

When you create space for new housing only in a small set of neighborhoods, the land in those neighborhoods that a developer must purchase to build that new housing is suddenly worth a lot more money.

There are renters everywhere—even in Five Points and Malvern Hills. If you suddenly allowed taller buildings with more lot coverage and/or more homes inside in those places, the land there would likely increase in value. And so a landlord renting out a crumbling bungalow on an 8,000 square foot lot that is walking distance to Haywood Ave. might decide to take a leap, and sell or redevelop that land, which might see that bungalow torn down.

But if you upzoned most of Asheville at once, that land value increase wouldn’t happen, at least not as strikingly, because builders would have more options to choose from. This also means that more vacant lots would be on the table. All things being equal, a lot with no tenants is going to be cheaper for a developer to purchase.

So it seems we are again faced with a contradiction. We want to be more pro-housing in less vulnerable areas, but we also want to use “broader geographic application” (97) to mitigate displacement. Furthermore, here’s what the Displacement Risk Assessment says about the question of limiting pro-housing reforms in more vulnerable areas:

It should be noted that choosing to not permit [missing middle] housing in [core neighborhoods near transit and/or retail] is not a valid anti-displacement strategy. Limiting potentially more attainable housing types in a particular area is likely to have its own exacerbating effects on displacement pressure. [Missing middle housing] has an important role to play in a multifaceted approach to reducing displacement pressure (126).

In more plain words: if we shouldn’t prevent modest multifamily housing from being added to wealthy neighborhoods, we shouldn’t be preventing them from vulnerable neighborhoods either!

The Displacement Risk Assessment goes further to press the idea that “missing middle” reforms are a solution, not a problem, to the housing crisis. It actually lists such reforms in its catalog of “anti-displacement strategies”! (Remember, we said above that the image leaves us hanging as to what those strategies might be.)

So we’re now full circle. Or maybe we’re back where we started? Pro-housing reforms, the image suggests, lead to good stuff, but also maybe potentially some bad stuff, which we can mitigate with . . . pro-housing reforms!

Now, it may be that we need to distinguish between different kinds of pro-housing reforms. What this image might be suggesting is that if some pro-housing reforms, if too extreme, may cause unintended consequences, then it’s the distinct characteristics of middle housing reforms—namely, their moderateness—that allow them to prevent extreme disruption.

I don’t think anyone’s talking about dropping a Hudson Yards on top of Shiloh. But housing and land use are personal, and important, and scary, and I appreciate that this distinction might need to be driven home.

But I don’t think that’s what’s going on here, at least not exactly. It just feels sloppy. And that leads me to the next part.

2. The Anti-Displacement Study is Muddy: Here’s How This Image Might Have Been Presented More Clearly

I do think that this image, and some of the surrounding context of the Displacement Risk Assessment, makes some sins and omissions. As a result, the picture they present may be muddier than need be.

First, I might quibble with some of the language in the image. It states that “in some cases,” research suggests that new construction increases localized displacement in vulnerable neighborhoods. The truth is that an overwhelming majority of research suggests otherwise. Housing policy experts describe this a situation where often such neighborhoods are already facing “late stage” gentrification. A housing shortage has fully matured, and any solution is going to present as too little, too late. The problem isn’t new construction, it’s that there hasn’t been been enough of it already.

Second, even in such cases where pro-housing policies—acutely applied—do lead to churn and teardowns (and to be clear, I do believe that this is something that happens!), policy experts tend to agree that it’s technically not the presence of new buildings that creates the displacement, but rather the change in land values. This seems rather nitpicky, but I think it’s an important distinction. While new buildings do often bring new neighborhood amenities that can make a place more desirable, recent studies suggest that the “amenity effect” is easily cancelled out by the “housing effect” brought by that same new construction. So the image under discussion would have been more accurate if it had stated that “upzoning” rather than “construction” was the alleged source of the problem. (Though as we’ve discussed, such a claim has its own serious issues.)

Why is this important? Setting the question of “missing middle” reforms aside, making new housing construction into a potential bogeyman puts us in the spot that the city was in a couple of years ago, when the question arose about building a whole bunch of mixed use stuff in the old K-Mart parking lot on Patton Ave. Activists were afraid that new housing on Patton Ave would speed gentrification in their nearby community. Now, that land has been set aside by Ingles to be a suburban style shopping center, and the housing situation has only gotten worse, and city councilors have come away with the wrong message.

Finally, it might have been worth stating a simple fact: development follows demand. (In other words, it follows land value.) Given a choice to build on a plot of land in Five Points or Malvern Hills, and a similar plot of land in Shiloh or S. French Broad, and given that those plots could be developed to equal degrees, capital is going to seek out the safer bets in the former locations over the latter. The cases in other cities where you do see a big fancy development dropped on a poor neighborhood tend to be the cases where the adjacent wealthy residential neighborhoods are protected by the most egregious exclusionary zoning regimes.1

What this means is that there may be little effective distinction between only upzoning Malvern Hills and Five Points and upzoning broadly across the city, so long as we include those high value neighborhoods. In other words, there is no contradiction between the image’s emphasis on targeting “low vulnerability” neighborhoods and the study’s paragraph that implores the city to allow “middle housing” everywhere. (There is one important distinction, and that is what the study’s authors implored as noted above: that vulnerable neighborhoods will actually benefit by having middle housing types on the table for infill as their own population needs grow.)

Understanding all of this, the scary image in question is telling us something pretty simple:

- Upzone for (and otherwise incentivize) missing middle housing.

- Do it broadly, and include the highest value neighborhoods (as long as they are near downtown and/or retail, bus lines, etc.).

- The more anti-displacement measures we can subsidize or otherwise implement in addition to broad and relatively moderate pro-housing reforms, the better the outcomes will be for the city’s most vulnerable residents.

Missing middle reforms are a safe bet. They are the least we can do right now to solve our city’s housing crisis, the cause of our housing displacement. And this brings me to my final point, that the Displacement Risk Assessment doesn’t do a good job of defining “displacement,” what it encompasses exactly, and what its causes are. There is a lengthy section in the study with all sorts of maps showing which Asheville neighborhoods are undergoing demographic change, and which are experiencing rising housing costs. But it doesn’t really explain the mechanisms through which any of this is happening.

When we only talk about “displacement” in the context of pro-housing land use reforms, or in the context of “new construction,” we reinforce a myth that many people bring with them when they come to these discussions—that displacement is caused by change, period.

This damn image has been bugging me since the spring, and when I talked to people about the city’s Missing Middle Housing Study, I wanted to ignore its presence altogether. It now seems clear to me that it’s not enough to avoid talking about it—to simply talk about the benefits of more apartments and more walkable neighborhoods and more “attainable” housing types. Rather, our city staff and electeds really need to try to take on these misunderstandings head on. As I’ve stated before on here, displacement is happening now, and the housing shortage is overwhelming the problem at root.

-

For example, Alex Hemingway wrote recently in Jacobin of this phenomenon in Vancouver, British Columbia. Similarly, recent examinations of New York City’s Bloomberg-era land use changes have stressed how limits on change in some neighborhoods had a big impact on how change was experienced in other ones. ↩

This member commentary post does not necessarily reflect the views of Asheville For All or its members.