Building Dense Multi-Family Housing in Vacant Lots Does Not Cause Displacement (or: How to Misinterpret an Affordable Housing Study)

November 29, 2023

This member commentary post does not necessarily reflect the views of Asheville For All or its members.

Earlier this month, the Citizen-Times reported on a presentation by Thrive Asheville, where that organization presented some results from an ongoing study about inequity in Asheville’s housing market.

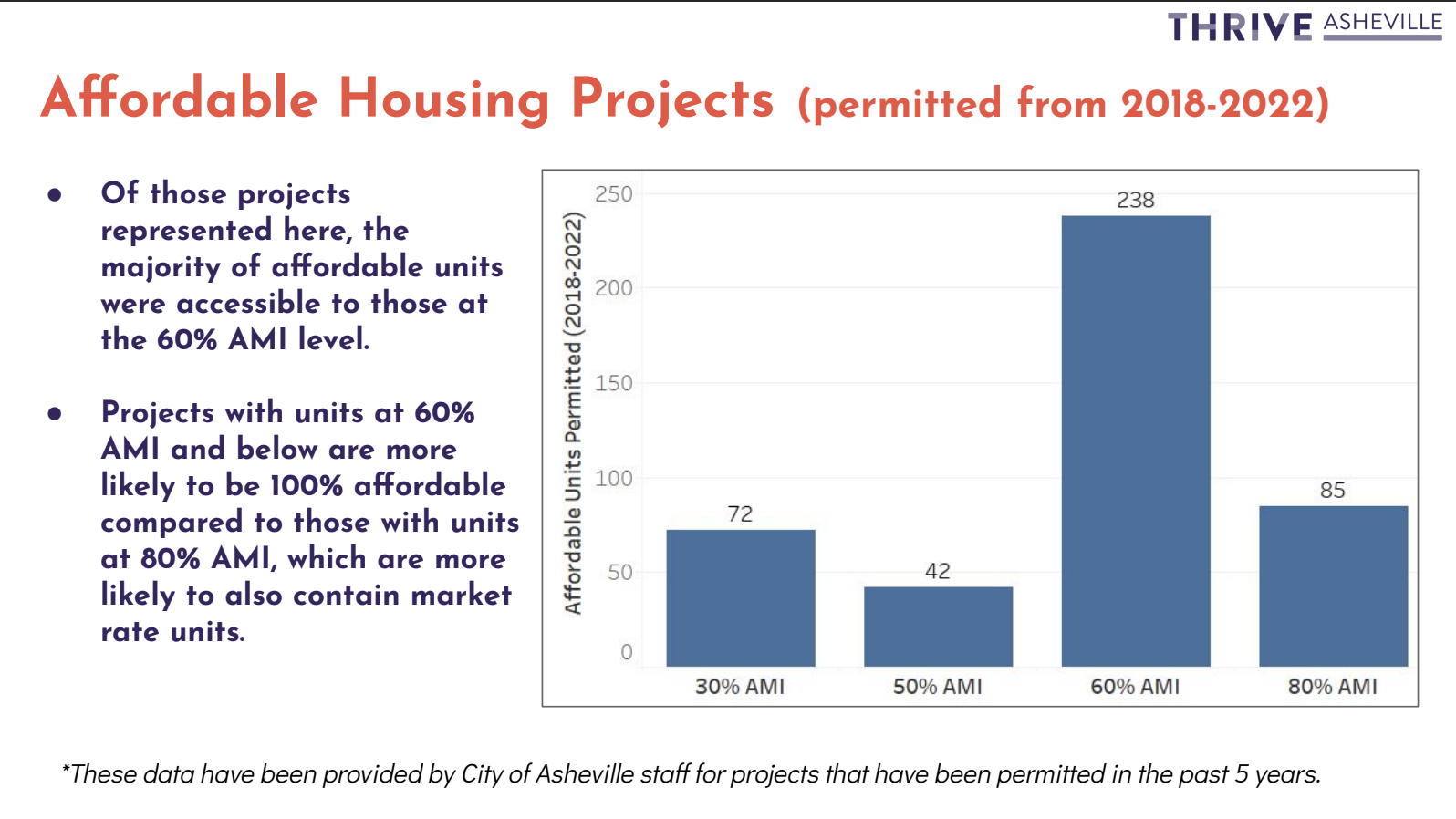

The study, the Citizen-Times suggests, shows that Asheville’s “affordable housing” policy may “exacerbate racial and gender gaps.” That’s because incentives such as the city’s density bonus tend to promote the allocation of subsidized homes at 80% of AMI (or area median income), rather than 30-60% or lower. So policies geared towards regulating affordability are helping people that need it, but they may not be helping people that need it the most.

A chart from Thrive Asheville’s recent presentation.

Following a discussion of some of the study’s findings, the article then quotes City Councilor Antanette Mosley, who interprets the findings as saying that building new dense, mixed-income housing will cause “gentrification.” She gives an example of the former Kmart parking lot on Patton Ave., which was once planned to become a mixed-use development, as a case where adding more homes to a plot of land that had none before would have sped up displacement. (That lot is now destined to become another suburban-style shopping center anchored by an Ingles supermarket.)

So let’s talk about how this report from Thrive might have been misinterpreted.

What Thrive Is Saying Makes Sense . . .

Again, at the core of Thrive’s data is an argument about gaps. Given a set of resources that are severely supply-constrained, if you take extra effort to provide those resources to one group of people, but aren’t able to provide those same resources to another group of people that have higher needs, of course you are going to create a gap between those two groups.

This makes sense, and we should take its implications seriously.

. . . But Thrive Is Not Saying We Should Stop Building Homes

It’s important to say that Thrive’s report is focused exclusively on analyzing programs that incentivize or create so-called “capital-A affordable housing,” which is to say, subsidized and income-restricted homes. In other words, it assumes that other factors that affect housing costs and options—particularly those that affect the majority of working families of all races and ethnicities that do NOT live in subsidized homes or receive vouchers—are static. Including overall housing supply.

So the problem with the councilor’s interpretation of the data is two-fold.

First, it conflates the analysis of a particular gap with an analysis that would look at broader trends of instability. Gaps appear all over the place, depending on how you look at a set of data. There is undoubtedly a gap between the lowest incomes and the ones that are next highest, and there is undoubtedly a racial gap that is historically and structurally constructed and reconstructed over time.

But there is also a gap between homebuyers and tenants of all kinds, between land-wealthy baby-boomers and struggling young professionals whose incomes are eaten up by housing costs, and there are dozens more gaps that we might find depending on how we slice the data. Eliminating gaps is a wholly important and worthwhile endeavor. But it makes little sense to eliminate a gap between the lowest and next-lowest incomes, for example, if it means bringing the latter group down rather than trying to bring both groups up.

But that’s what the councilor’s suggestion for preventing new dense, multifamily, mixed-income would actually do.

Why? That brings us to the second problem with the councilor’s interpretation of the research. She ignores the larger role of housing scarcity in the construction of our gaps and in the peculiar place that “affordable housing” policy makers are in, given this broader context.

To be clear, we absolutely should use data-driven analysis in order to help our most vulnerable populations more effectively. But we should also understand the constraints that we impose on our “affordable housing” programs by limiting overall housing supply, and how those broader constraints mean that policy makers are forced to make difficult choices. The less housing you have overall, the greater amount of the population is vulnerable to scarcity and rising costs. And you can only help so many people with subsidies that need to be paid for.

So preventing new homes in the old Kmart lot—or anywhere else—means that you may have prevented a gap between the two lowest income groups. But that’s only because you’ve made it harder for both. That is, you’ve exacerbated a greater gap higher up the chain. And you’ve made the gap bigger. That’s because of how housing markets work like a game of “musical chairs.” Some people might need more help than others grabbing a chair. But you’re never going to make things better by taking more chairs away.

When homes are scarce, those with the most wealth are able to swoop in and “outbid” other buyers, causing costs to rise across the board and making the people at the other end of the wealth spectrum more likely to be displaced.

To borrow and paraphrase an argument made by the inimitable Black sociologists Barbara and Karen Fields, we shouldn’t be aiming for a city where Black and white residents alike are shut out equally by scarcity, property inflation, and segregation. Rather we should target the root of the problem that is burdening all of our working families. We can do this while being attentive to the needs of the most vulnerable populations too.

The plan for a walkable neighborhood with multifamily housing in the former Kmart lot on Patton was shelved for what will be a suburban-style shopping center. What gaps are exacerbated when we don’t allow housing to built for anyone at all? (Image courtesy of the City of Asheville.)

But that means rejecting scarcity-based, zero-sum thinking. We assume that scarcity is a given, but it’s a choice. In our housing policy discourse, sometimes we assume that the only new homes that are going to make a difference in our crisis are income-restricted homes. But this simply isn’t true. There is no trade-off, no zero-sum, between adding homes for different demographics. It only appears this way because we are purposefully restricting, obstructing, or disincentivizing the supply of new homes in the places where we most need them!

The truth is that the fastest way to make Asheville a place that only white, wealthy residents can afford is to block new multifamily housing from being constructed.

Again, the vast majority of low-income, working people do not live in income-restricted, subsidized housing, and the vast majority aren’t able to utilize housing choice vouchers either. There simply isn’t nearly enough money at any level of government to provide non-market homes to all of the people that are rent- or mortgage-burdened. But the evidence is crystal clear that to make housing more attainable and affordable for these folks, we need to increase the supply of all kinds of homes, in greater density, in the places that are highest in demand and opportunity.

And when these kinds of homes are allowed to be built in abundance, a funny thing happens: the cost of subsidizing homes for the people that are more apt to fall between the cracks goes down.

The UCLA Housing podcast recently had a couple of experts on the show to discuss how increasing market-rate housing can lead to conditions in which subsidies that target lower-income renters can be made more effective. If we diminish the conditions that cause market-rate rents to rise, and make rents relatively cheaper, then the government has to spend less money on subsidies that need to cover the difference between “affordable” rent payments (those that are capped at 30% of a tenant’s income) and the rate that landlords charge. And if the government saves money on each tenant, it can help more tenants.

This is notable because even if simply increasing the supply of homes, which we know reduces rents and home prices across the income spectrum, does NOT reduce racial or class gaps per se, it’s still effective in empowering governments to then target those gaps more economically.

The study discussed on the podcast was observing housing choice vouchers, but there’s no reason to believe that our local programs like LUIG wouldn’t be affected in the same way. Build more homes, reduce the relative cost of renting, and those programs would have the potential to go further and reach more people. Choosing who gets left behind in a landscape of scarcity is a game with too many losers. We need to change the context in which we have to make tough decisions around “capital-A affordable housing” spending, and that means allowing much more multi-family housing to be built, period.

This member commentary post does not necessarily reflect the views of Asheville For All or its members.