Housing Is a Community Benefit

This member commentary post does not necessarily reflect the views of Asheville For All or its members.

Something terrible happened last year: Grata Pizzeria, the new Neapolitan-inspired pizza place on Haywood Road in West Asheville, closed down.

There are likely many factors that contributed to its closing, but I seem to remember that when it happened, the owner was quoted in the paper as saying that one factor was a lack of foot traffic. There just weren’t enough people stopping by.

Having an excellent pizza place in one’s neighborhood is a great community benefit, I think nearly everyone would agree. But that in turn means that the customer base that is necessary for such a place to exist is itself a community benefit too.

In short, for a lack of a sufficient residential population, we West Ashevilleans lost out. More housing in your neighborhood is undoubtedly a great benefit if it means Neapolitan style pizza.

* * *

Speaking of neighborhood benefits, at least a couple of city council members have recently expressed the desire to have a “community benefits” table for the development of large multifamily residential projects.

I have to confess that my thoughts range from ambivalent to concerned about the idea, even though I understand that it may have its practical benefits in terms of fast-tracking large multifamily developments that would otherwise get hung up on the City Council docket. Likely, the devil will be in the details.

And I think that I want to write about some of those possible details at some point. But for now, I want to make a kind of tangential argument: that whether or not a benefits table is a good idea, we need to acknowledge that infill housing already is a community benefit.

* * *

If you’ve never heard of a “community benefits table,” what you need to know is that the idea is plucked straight from how our city deals with the development of new hotels.

After Asheville’s hotel moratorium expired a few years ago, the city initiated a new process whereby hotels could be built—within the confines of Asheville’s “hotel overlay map”—as long as the new developments checked certain boxes. The project could contribute to an “affordable housing” fund, provide public parking for nearby businesses and amenities, or the hotel could promise to pay its staff a living wage, for example.

Importantly for hotel developers, the community benefits table allows them to circumvent City Council review. This effectively takes politics out of the process, and leaves only the usual administrative permitting hurdles that come with any kind of “by-right” development.

Here I want to point out the tension going on. On the city’s webpage that explains the hotel benefits table, it begins by noting that North Carolina “does not allow municipalities to outright ban future hotel development.” This webpage is in effect suggesting that “hey we can’t ban them, so this is the next best thing.”

This hotel policy comes from a place of concern about a possible oversupply, not that of a shortage. Presumably, it seems, Ashevilleans don’t like hotels. At the same time, the policy is described as a way to move development along with “transparency and predictability.”

Homes, we should be reminded, are not hotels. Contrary to some of Asheville’s popular commentators, not all “development” is equal. And so one of my biggest concerns about the proposed idea of a community benefits table for housing is a discursive, or rhetorical, one; it’s about the connotation, in other words. The idea takes the truism that hotels are a kind of trouble that needs to be offset, and transfers its logic into the realm of multifamily housing. It makes apartments and hotels appear to be things of a kind.

Whatever you think about hotels—and to be clear I’m not necessarily in the anti-hotel camp—multifamily homes need to be understood by the public as something good as well as something distinct from short-term lodging.

* * *

So why is infill housing a community benefit?

Here’s a laundry list of reasons. Any of these points warrant an essay on their own, so I’ve tried to be brief, and to include links to deeper dives.

Lower housing costs for existing residents seeking to move nearby, and lower costs for those trying to stay in their homes.

Pro-housing advocates make a big deal out of saying that new housing benefits the people that don’t have a voice in neighborhood decisions because they don’t live there yet. But new infill housing helps people that live in the neighborhood too. I wrote earlier this year about my own experience finding new housing in my neighborhood when I was displaced. And of course, evidence is clear that new housing in a neighborhood helps keep rents of existing buildings down.

Furthermore, no one likes to see homeless people in their community. Reducing the housing crunch means less people falling into homelessness.

More socioeconomic diversity, more friends, more “character,” and better art.

Socioeconomic diversity is a community benefit, frankly, because it means your neighborhood is going to be less boring. Character, we like to say, is created by characters, and so allowing for infill housing, which means allowing for more housing types, brings in more types of people with it.

Any of these people may become a new friend or acquaintance, someone to dog-sit or water the plants. And that’s good. We can speculate on why Americans have become misanthropic when it comes to land use. (Is it parking? A mistaken understanding of environmentalism?) But I still think life is more interesting when there are other people around.

Furthermore, as Ned Resnikoff argued in an excellent recent essay, more infill housing means more and better art.

Walkability and more businesses.

As I mentioned above, if we want more cool stuff in our neighborhoods, we need to bring in the people to support that stuff. It’s not uncommon to hear questions like “when will South Asheville get a Trader Joe’s?” around town. The obvious answer is that if we keep blocking new infill housing, such things will be unlikely!

The anti-housing crowd might inevitably push back—those things bring traffic and congestion. (Just look at the Trader Joe’s parking lot!) But it doesn’t have to be that way with well designed land use rules and incentives. The idea behind walkability is that with enough housing in close proximity, we can all skip sitting in traffic because every neighborhood can have a Neapolitan pizza joint, and that also means that even if you are driving to a local amenity rather than walking, biking, or taking a bus, it’s still a much shorter drive than if you have to go across the city.

Speaking of alternative modes of transportation, I hope it’s evident that the viability of public transportation depends on housing density. The more homes we have close to jobs and amenities, the easier it is to connect people to the places that they need to go, and the more attractive it becomes to take public transit rather than to drive. (Public transit is a community benefit for a number of reasons; it actually helps drivers because it takes other cars off the road, but most importantly, it’s a benefit for the nearly one-tenth of Asheville families that don’t own a car.)

When I lived in Minneapolis, I lived in a neighborhood called Lowry Hill East, which was rich with “middle housing” as well as single-family homes. This wasn’t Manhattan; many people owned cars, others like me did not, and there was a mix of families with kids, young professionals, and students. There were no high-rises or Soviet-style apartment blocks. But it was incredibly walkable—I could get to dozens of coffee shops and bakeries, two bookstores, two movie theaters, and three grocery stores within a ten minute walk.

(For what it’s worth, that neighborhood has grown a bit since I left, and it now includes its own urban-format Target!)

A larger tax base for better amenities, services, and infrastructure.

Property taxes are good, I’ve noted elsewhere, but no one wants to see them go to waste.

Urban3, a planning firm based in Asheville, has gained national attention by showing that sprawling, low-density, and car-centric land use results in cities spending a lot more money on basic infrastructure than they get back in tax revenue. In short, suburban-style land use is subsidized by denser patterns of apartments and businesses. (This is true even when owners of single-family-homes have relatively high property values.)

This is in part because maintaining roads, sewers, and other services costs more money per resident when those residents are more spread out. Of course, this flies in the face of a commonly voiced anti-housing argument that “infrastructure” will suffer if apartments are built, or that dense housing is “unsustainable.” In fact, it’s the reverse. So when a land-wealthy North Ashevillean complains about new housing going up on Charlotte Street, and invokes their status as a “tax-payer,” they’re speaking from a place of unearned privilege. It is their presence, fiscally speaking, that might offer only a negative “community benefit.”

The best way for us to sustain a city with functional, sustainable infrastructure is to create more neighborhoods that can be maintained with the funds that are generated from that neighborhood’s own tax base.

To be sure, “your city can be more fiscally-minded” is not the most compelling argument for housing abundance. Personally I rolled my eyes when I first heard it. But ultimately this is about the capacity for delivering public goods, and public goods are good.

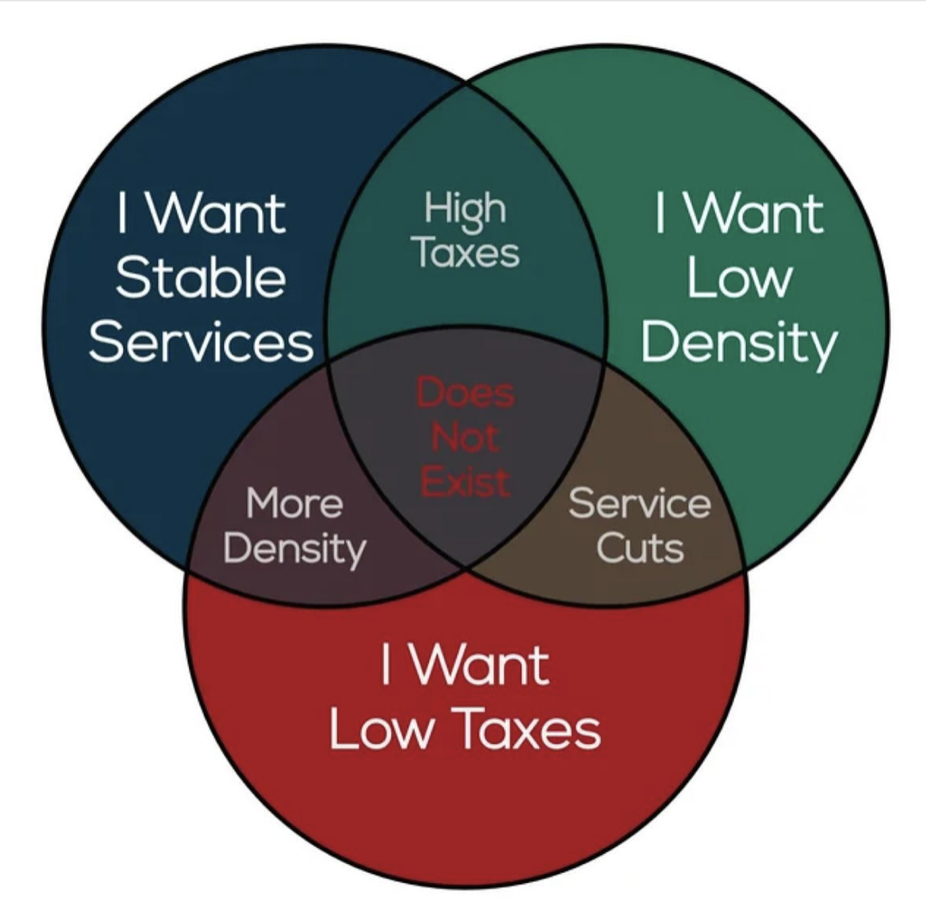

Ashevilleans want it all. We want swimming pools and arenas with working HVACs and parks and greenways and pickleball and clean sidewalks and safe streets. It’s sometimes said that advocates for maintaining suburban land use in high-demand places want the benefits of a more rural life but with all of the amenities of a more urban one. I think this is an astute observation. We don’t need to ban single-family-homes to acknowledge that we can all benefit from encouraging and incentivizing land use patterns that will mean that the growth of our neighborhoods will redound to more public goods and reliable infrastructure for us.

And just to circle back to the point about transit viability: there’s an important discussion happening about extending out Asheville’s bus lines, and making service more frequent. Because of an outdated zoning code combined with anti-housing sentiment in Asheville’s core neighborhoods, we are seeing multifamily housing being built mostly on the region’s peripheries, in places like South Asheville where there is less service, and any bus rides downtown will take some time.

Needless to say, we can get more bang for our buck if we increase the base of transit users in places where service already exists, and also that it makes more fiscal sense to extend service to neighborhoods with greater concentrations of people—especially when those people might be living close to the jobs and schools that they might head off to each day.

Feeling good about reducing community contributions to the climate catastrophe.

Talking about the climate crisis might be a bit of a cheat, since it’s not really a local thing.

But we know that infill housing is a necessary step towards mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. (See also the UN’s IPCC recommendations.) And as Bill McKibben wrote in an article about land use and development opposition, “we don’t just live in a community; we also live on a planet.” Surely, as much as the very idea of a “community benefit” is to address the needs and wants of a local community, we can’t be blind to the way that a potential policy change could improve things for both ourselves and others.

* * *

Now that all of that is out of the way, I want to acknowledge that all of the above may be true, and it could still be a good policy to implement a housing benefits table if it means that more infill projects with more homes will be approved without each project having to go through a lengthy and costly political approval process.

But I’m not sure. So I’ll try to share more on this subject soon.

This member commentary post does not necessarily reflect the views of Asheville For All or its members.